Finance and Miscellaneous

Miscellaneous Bits and pieces not quite warranting their own dedicated pages

Actively Managed Funds

This is a mixed bag and one that non-fiduciary advisors are often likely to try to push you into, whether it’s their own brokerage funds or ones they make commission on, especially in the case of non-fiduciary advisors.

If you’ve agreed with in general the ‘3 fund portfolio,’ do you need to add in actively managed funds? No, not really, but it’s reasonable to take some reasonably small percentage of your overall investments into a ‘dealer’s choice’, like 5-10% ‘your choice’ or ‘experimental investments.’ Maybe that’s bitcoin, maybe it’s a tilt (covered further below on this page) towards some specific sector, maybe you find a fund matching those preferences and it’s actively managed.

Do bear in mind the usual refrains, as actively managed funds tend to have higher expense ratios and fees, as well as more annual turnover rates with risks of unexpected (and active) realized gains across the year.

-

A majority of active management beyond indexes tend to not sustain gains over a period of time when compared to broader index investing.

-

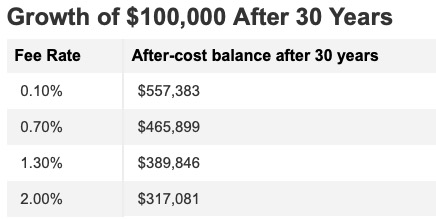

Any fees you’re paying in higher ERs, advisor fees, etc. is less money invested for you and less compounding over time.

Actively managed funds will generate higher turnover and gains and losses - and in most cases, are generally better off being left in a tax advantaged account. The main exception might be those specifically also managing tax loss harvesting. You can also check for any managed fund what the anticipated annual ‘tax cost’ is for the fund - if it’s higher than .5% or so - you’ll want to probably keep it in tax-advantaged.

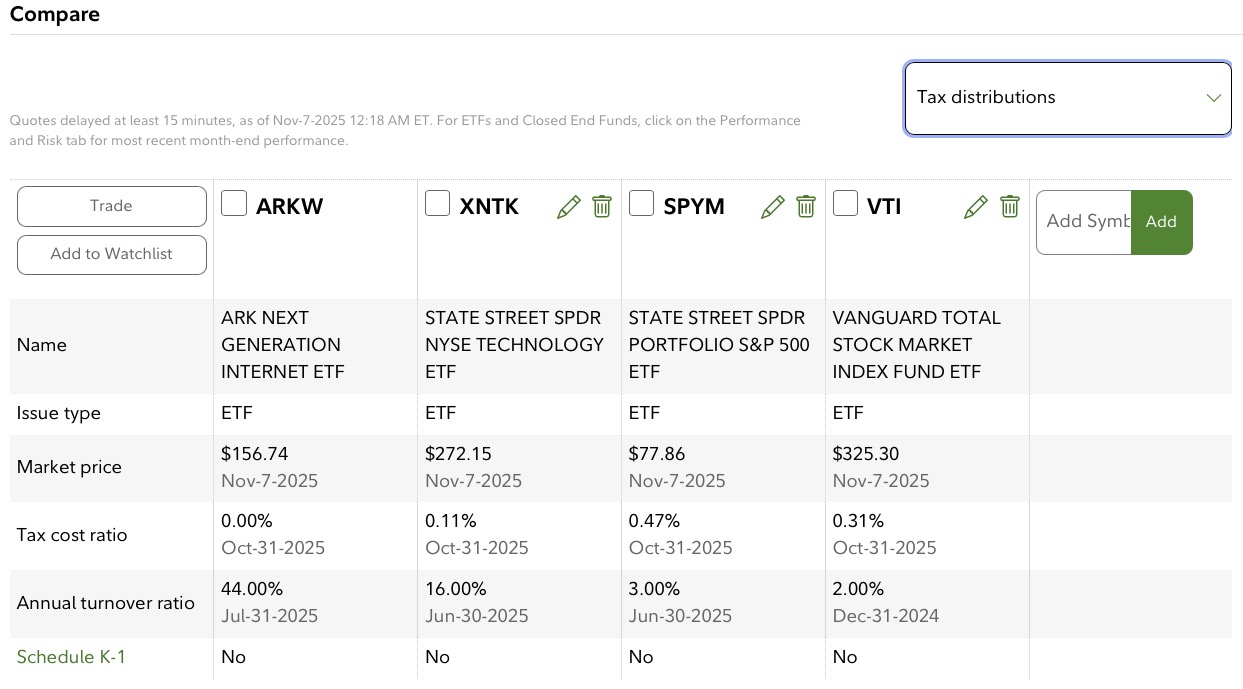

You can check the expense ratios via basic fund information, as well as the annual turnover rates. You may need to dig in a bit to get to tax costs, which on Fidelity annoyingly isn’t in the basic fund info, but if you go into comparisons, you can then select tax distributions to get to the tax cost and turnover rates. I do wish this were shown in the basic information for all funds, but it can be found, as well as via fund prospectus.

In the case shown to the right, you can see ARKW, which is an actively managed fund, which is focused on technology, has a fairly high annual turnover rate, but surprisingly a low anticipated tax cost, so if you were considering some additions to your core 3 fund portfolio, this one could be held in a taxable account if you so wished - most likely in small quantities, as I wouldn’t consider this to be a likely long-term/decades holding, so even with the fund not generating expected taxable income, selling out of the position will certainly generate potential realized gains - or losses.

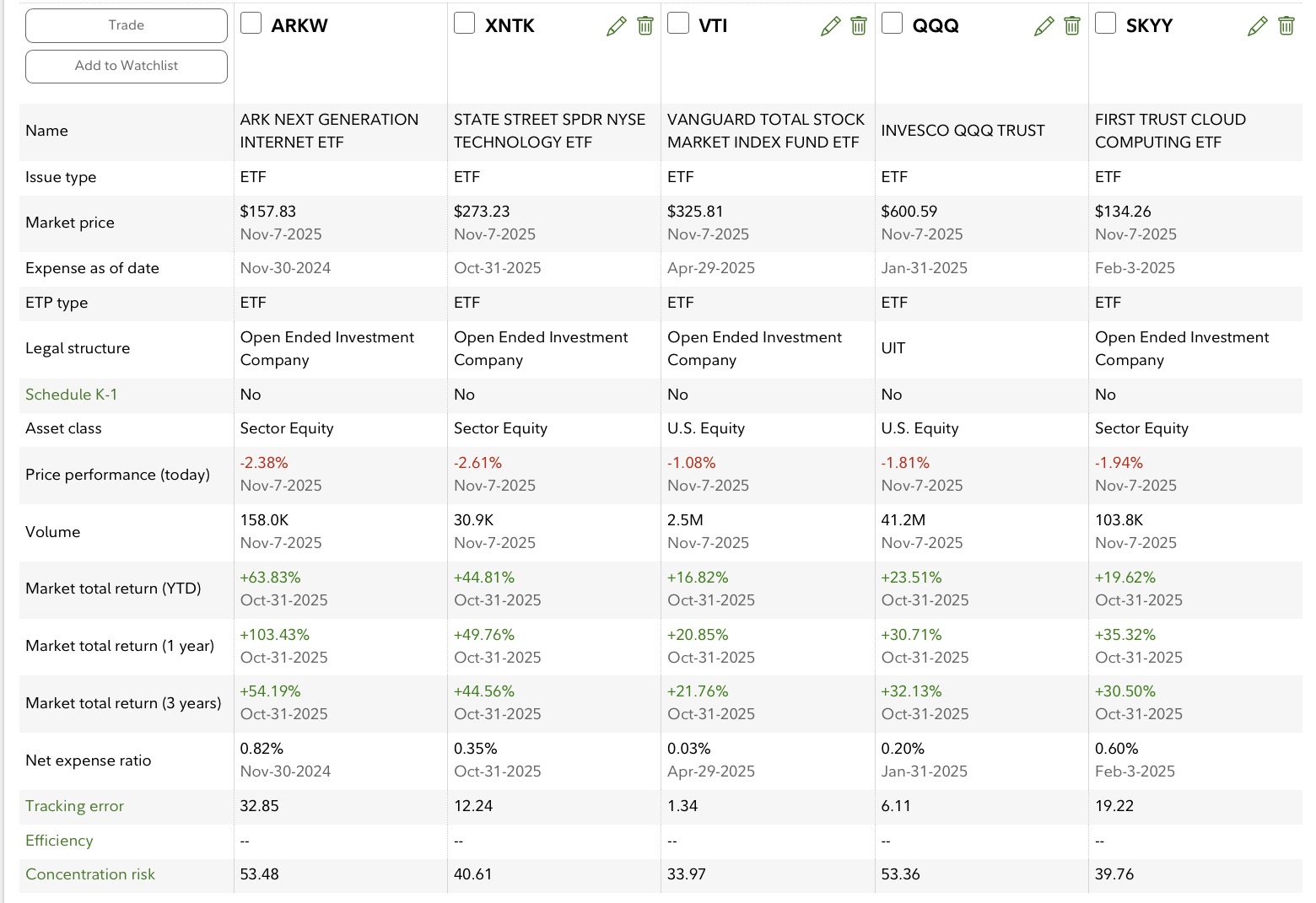

It also has an obnoxiously high expense ratio of nearly 1% at .82. In the chart to the right, SKYY and XNTK are somewhat similar technology sector focused funds, with QQQ being a specialized more focuses US equity holding. Of course, the returns on ARKQ look impressive, with some bitcoin exposure as well if you drill into the composition, and currently Tesla (TSLA) as their top holding by a few points at almost 10%. Personally when I look at their holdings, this is very much a ‘Hail Mary’ super-focused (it has ~50-60 holdings in total) aggressive play in the tech sector.

It’s your call on managed funds. I do hold some ARKW but am going to reduce my exposure over time personally, as I expect a market correction to happen and I don’t personally think the Tesla train is going to continue upwards indefinitely. I also consider them part of the ‘dealers choice’ grouping as a low percentage of my investments that can either hit the stars or crash to the ground - or perhaps both given enough time. YMMV - you do you.

Managed funds may make some sense in some conditions, but in general, I’d say they’re a shorter-term play as over decades they’re quite unlikely to outperform equivalent indexes, so may require more active monitoring, and may well enter into the whole ‘market timing’ philosophy we want to avoid as much as possible, and certainly when startng out. Do make sure to check tax costs, and anticipated capital gains to determine if you go down this path at all, if tax-advantaged or taxable is a more appropriate place for the holding. With something as laser-focused as ARKW, I wouldn’t recommend it in general, but even without the tax costs, I expect to sell out of it which will in turn generate realized gains (as of today anyway) of some significance, which I’d then need to offset via loss harvesting with this sitting in a taxable account.

Advisors and Brokerage Fees

This is a mixed bag and one that non-fiduciary advisors are quite likely to try to push you into, along with specific funds which may very well have higher expenses than equivalent other offerings. This is not always the case, but if they are at a specifc brokerage, that by itself will determine what funds are easily, readily available to them. Some broker-specific funds like FZROX for example, are pretty decent (in a tax-advantaged account for FZROX in general as a mutual fund) but that may not always be the case, and of course, they are charging you their own either direct ‘expense ratios’/fees themselves or by directing you into different brokerage offerings.

There are different types of offerings and combinations:

-

Manage Everything - all of your investment accounts or all at a given firm, or a significant portion (e.g. they may not for example, manage a 529 plan actively in ‘most’ cases.). Assume anywhere from .5-several percent in advisor fees.

-

Directing into specific brokerage managed accounts, e.g. IRA management for .5-.8% (examples), or an actively managed specific purpose fund such as large growth for 1%, or again the ‘we’ll cover it all’ for different percentages.

There are some situations where paying an advisor might make some sense. If you’ve inherited accounts from someone, or have unusual circumstances such as declining health, or are unable to handle periodic rebalancing, it might make sense to use an advisor, or a managed account. Any of those truly ’set and forget’ where you may be happy with a target date fund, which is already paying expense ratio fees - of course, don’t need an advisor.

It might make sense in the inherited accounts situation to consider paying for a one-time evaluation if you are unable to do the research yourself, or if you’re unable to determine what asset allocation and risk level you are comfortable with.

If you decide you want to go down this path, do realize that it’s worth shopping around on advisor fees, and considering the significance of what’s involved here (your future financial health), you don’t need to settle for the first one you call, including if, for example, you simply aren’t a decent personality fit, if they blow off your questions, etc. You’re paying this person to help improve your future, and not everyone is going to be a fit.

If you do consider using an advisor, make sure they are a fiduciary !!

I really can’t repeat this one enough. A fiduciary is legally bound to act in their clients’ best interest. Non-fiduciary advisors are not, and may leverage that into higher expense funds and a larger number of transactions they may earn commissions on. Of course, this doesn’t mean a fiduciary will lead you to Year-Over-Year 50% gains, nor that a non-fiduciary will never do so, but don’t start with a deck stacked against you. If you’re going to engage with an advisor, ensure they are a fiduciary. The same applies to specific account management. For example, I believe all of Fidelity’s management options have fiduciary responsibility, and it’s likely some other bigger institutions such as Vanguard do as well but always check, and preferably see it in writing.

Account Fees and Fund Expense Ratios

Specific accounts from your employer-sponsored 401K/IRA/403b may have their own fees, usually applied monthly or quarterly. Your employer may cover these fees, meaning no net expense to you, or may not, and the account fees range quite a bit. Fidelity and Vanguard charge no fees for most if not all of their accounts, although they do offer various managed accounts or advisory situations which can incur fees.

A new employer’s 401K fund I had considered doing multiple rollovers into turned out to have a base fee nearly .5%. Considering their relative lack of ‘management’ and fund selection, I chose to take my rollover funds elsewhere, while still contributing in order to receive my maximum employer matching funds. You can read about that and rollovers in general here if you’d like.

At the end of the day, some of the numbers like < 1% sure don’t sound like much, but take a look at the chart above for an idea of how much ‘fractions of a percent’ to 2% take money out of your pocket longer-term.

When you add up individual fund fees, then additional account or advisor fees on top of that, they add up and can literally steal hundreds of thousands of dollars from your retirement over time.

Some fees are unavoidable, and we collectively need to be ok with that. Your employer sponsored accounts are what they are. You should ensure if they give matching funds, you get what you can/max out their contribution as it’s free money, but there’s nothing saying you need to roll over more money into those higher-fee accounts.

Likewise, there is nothing wrong with taking (most) accounts out of management if you feel this is for the best for you, or to shop around for a better advisor or account. There is nothing stopping you from ‘firing’ your current advisor if he/she is loading you up on needless transaction fees or high expense ratios or their own fees, and moving it all to Fidelity, Vanguard, or another quality no-base-fees institution.

A majority of my current holdings fall into the .02-.09 range for fund expense ratios. I do have a few outliers like the aforementioned ARKW example as the highest at .82. I have a pair of specific sector-focused holdings in my ‘dealers choice’ holding percentage at .5 which simply had no comparable lower-cost alternatives, and you will see that in some cases if you add on to your core index fund holdings. However, 80% of my total brokerage holdings have a fee of ..02 up to .09, and at least half of the remaining are going to be transitioned to lower expense ratios as I do this and next year’s loss harvesting and rebalancing. It’s ok if you have a few outliers, but if a significant portion of your holdings are outside of this range - you had better be doing some comparisons and compare your returns to other options, as in most cases - you can do better. Don’t sweat the .02% on one index fund vs .03 on another too much - invest in whichever is easier (e.g. if one has a sales load or transaction fee, use the other one), but certainly look if lower expense ratio alternatives are available. If you find out there are, don’t bulk sell and re-purchase in a taxable account - you’ll need to plan this to balance gains and losses, but do consider making a plan as well as adjusting any new or auto-investments into the lower ER fund.

One thing to note - any administration or management fees for the account(s) from an instituion are coming directly from your pocket, meaning they are deducted usually on a quarterly basis, while fund expense ratios aren’t ‘billed’ and are reflected in the overall cost of the fund itself - to an extent it shows a relative level of efficiency, but does not present you with a ‘bill’ for holding the funds themselves.

If you have an advisor today, take a look at your holdings, and when/how often they are trading, and are they trading in funds with ‘sales loads’ or purchase transaction fees? Research the funds and look for alternatives to judge if they are reasonable trades and fees, or not. I’ve found a couple of funds at .6-.8% that were inherited that were easily replaced with not only much lower expense ratio funds (like .03-.08) but ones that in many cases had a long history of outperforming the ones being replaced. You don’t know if you don’t at least take a look and weigh the account, advisor, and transaction fees individually and added up, and make the right decision for you, but do take another final look at the above chart and always remember - each dollar paid to someone else is removing it from your future compounding of investments.

Market Timing and buying/selling ETFs and/or mutual funds

This is pretty broad overall category but we’ll simplify it a bit.

Mutual funds trade after market close at their NAV (Net Asset Value) price, so the same price effectively everyone both sells and buys at. It’s ‘simple’ and hands-off, which for many, many people - is a good thing. However, mutual funds are mostly only a fit for tax-advantaged accounts as they generate additional dividends and capital gains that can be unexpected for yearly tax filing and leave you with a surprise tax bill if caught unaware - so in general, keep them in your tax-advantaged accounts where those gains don’t matter until withdrawal.

Their ETF equivalents are more suitable for taxable accounts, but they trade just like stocks, meaning their prices fluctuate up and down while the stock market is open (9:30am-4pm EST), sometimes a fair amount, as well as in pre and after hours trading which we’re not going to get into here, but is a bit riskier/more volatile and has much fewer participants.

You can see in the chart below which is showing one of our oft-referenced core holdings, VTI(US Total Stock Market Index) in a single day’s worth of trading. It looks like a huge amount of movement, doesn’t it? Check the top center and you'll see the price ranged up and down almost 5 dollars (ranging from $324.97 to $329.63 and closing at $329.44). However, as the individual stock price is in the $300+ range, that movement doesn’t really amount to very much, in fact it’s pretty close to 1-1.5%. Of course, there are some days where there may be truly significant swings, but - OMG, when do I sell? Or buy?

In a way, this is one advantage that many of us have a majority of our investments in retirement and other tax-advantaged funds full of mostly mutual funds and you simply don’t touch it for the most part other than perhaps adjusting allocations and occasional rebalancing if you’re self-managing it - you’re less tempted to try to time the market, or worse, time the market during a specific day, or hour.

On your auto-investments, this temptation is removed from your purview. Just consider auto-investments to be ‘just like mutual funds’ - you purchase at the single price available at time of your next auto-investment. And that’s just fine.

Now, if you are re-balancing and need to dig into selling off some funds in your taxable account, and buying the ‘low’ percentage assets, or even just buying the low percent assets, you might want to take a breath here.

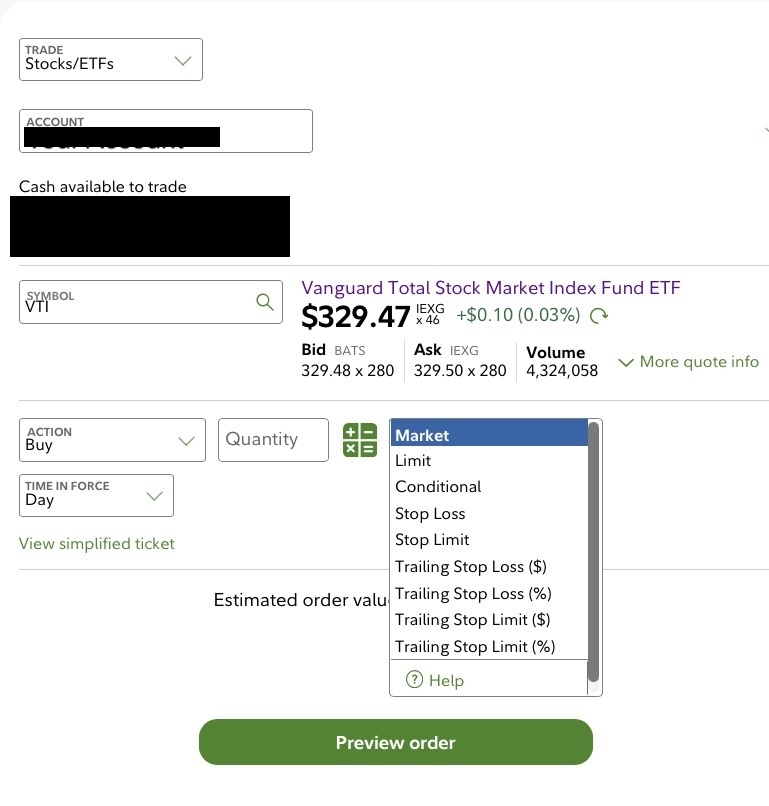

If you are nowhere near retirement, it all matters a whole lot less. If you are approaching or in retirement, and don’t have the stomach for it, this is one place an advisor may help by taking it out of your hands, especially if selling a significant amount such as a yearly or monthly expense selloff in the thousands of dollars range. Now, in the example above, the daily swing isn’t that bad. You can see up top as well, the bid and ask numbers - this means the people looking to buy are wanting to buy at $329.42 while a majority of those looking to sell are wanting to sell at $329.45 per share, or a 3 cent/$0.03 ‘spread’/difference. When you make a purchase or sale, you basically have two options:

-

Buy/sell at market

-

Bearing in mind it’s entirely possible the <current this second> bid/ask may have changed by the time you fill out the buy or sell form and submit it, this effectively says ‘make the first available purchase or sale at whatever the current ask/bid is.’ When an order (purchase or sale) is placed it goes into the queue. In other views you may be able to see how many bids vs asks there are, not just the bid and ask prices. Once it’s settled it will show in your orders history including the purchase or sale price. In general, I use the next approach, or try to, but if buying or selling $1000-ish worth, the above daily spread amounts to $15 difference in best vs worst, so in this situation it’s not a big deal either way.

-

-

Buy/sell with a limit order

-

This lets you set the specific number you’ll accept for either sale or purchase. The default may or may not be what you want, so always check the value being auto-populated. It will generally set to sell ’now or soon’ based on the spread of the bid vs ask numbers, but you can over-ride.

-

You can leave it as the default of the order being valid for ‘day’/today, or GTC/Good Until Cancelled.

-

Note that for buys or for sales, there is that ‘widget’ next to the quantity field (the sqaure fgrid with +, -, X and =). You can use this to set a dollar amount, and it will convert into a share count (based on the number it auto-populates for share price, which you can adjust

This is super-convenient when balancing, for example, you know that you’re $5000 low in bonds and want to purchase that specific amount for balancing. Now, if you’ve got time to wait, and are excessively anal, you can indeed fiddle with the limit numbers, or on the other side of things, you can just let it go at market. At lower amounts this really doesn’t matter much, but in a way, it is sort of an ‘added expense ratio.’ We all need to find our specific comfort levels. In some cases on things that don’t matter/not part of end of year tax loss harvesting, but for example, company RSUs, I’m more inclined to set GTC/Good Until Canceled Limit order at a specific number, and whenever it hits that day, a week or a month later, I’m fine with it, but in general for both new manual investments, rebalancing or tax loss harvesting, I pretty much make sure it’s executed the same day, as few of us have time for endless fiddling, guessing where it may or may not go in a day, or not.

If you are in or near retirement and are lower in your savings than expected or needed, this is potentially the time for an advisor as I can’t help there other than to say - unique considerations do exist, and you need to be comfortable with managing these things, or get someone to help. For those of us still in accumulation phase, the above and most of the rest of this section should remain relevant and hopefully useful, and hopefully for those approaching and in retirement as well, as far as general information goes, although they may choose to get some advisory help if that is what works best for them.

For a little bit more on yet another reason we shouldn’t get excessively concerned on either our auto-investments or relatively smaller adjustments from semi-annual or annual rebalancing efforts, let’s move on to the next section.

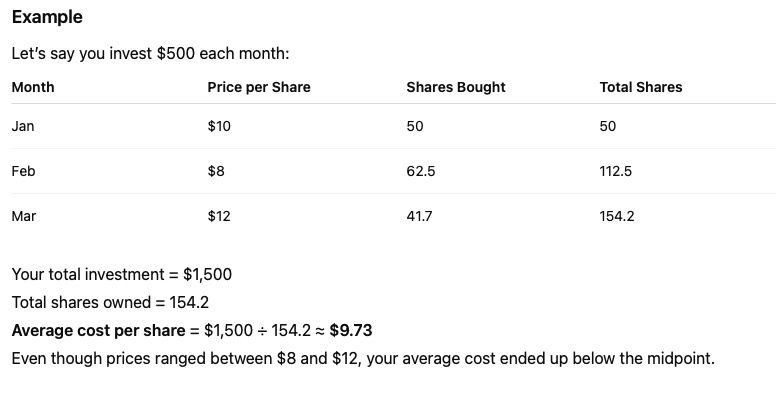

Dollar Cost Averaging

As most of our contributions are not generally truly large numbers, the concept of dollar cost averaging comes into play and helps us in numerous ways.

Recall the math behind the daily changes for VTI? That level of change really doesn’t matter much when in the day you purchased as we are looking for long-term, nearly 'set and forget’ levels of investment in the majority of cases.

When we are doing our auto-investment, they’re generally low numbers, and if they’re split across all of our allocations (US Stock, International stock, and Bonds or similar, at any given point you may be paying ‘more than last time’ for one asset while ‘less than last time’ for another, which in itself has a balancing effect of buying (more) low, and buying (less) high in shares while maintaining a constant amount.

You can see in the chart above the net effect of a fairly volatile stock or asset purchase over 3 months, and the net effect. As we aren’t hopefully day traders, this approach actually smooths volatility out a bit by effectively buying fewer shares of an asset that’s up and more that are down, as your allocations are hopefully percentage-based, or you can adjust them accordingly over time. It helps to reduce emotional decision-making and in nearly all cases, investing versus ‘waiting for the perfect time’ which may never come - will net better results. This mindset also helps with consistent and disciplined savings - over time, the collective market will absolutely have different assets hitting ups and downs, and rarely will ‘just sitting in out altogether’ be the right move. YMMV, but considering dollar cost averaging and a set and forget mentality (*aside from loss harvesting and annual rebalancing) can help grow your future wealth while also letting you ‘not sweat the small stuff’ and become more confident in your future. Note that on many platforms, ‘average cost basis’ is also shown within their tools.

Portfolio ‘Tilts'

You might recall from prior articles the concept of ‘dealer’s choice’ or taking some small percentage (like 1% up to a maximum of 10% or so) for you to have a playground, or add additional investments above/beyond your core 3 fund holdings, which should IMO retain the lion’s share of your investments.

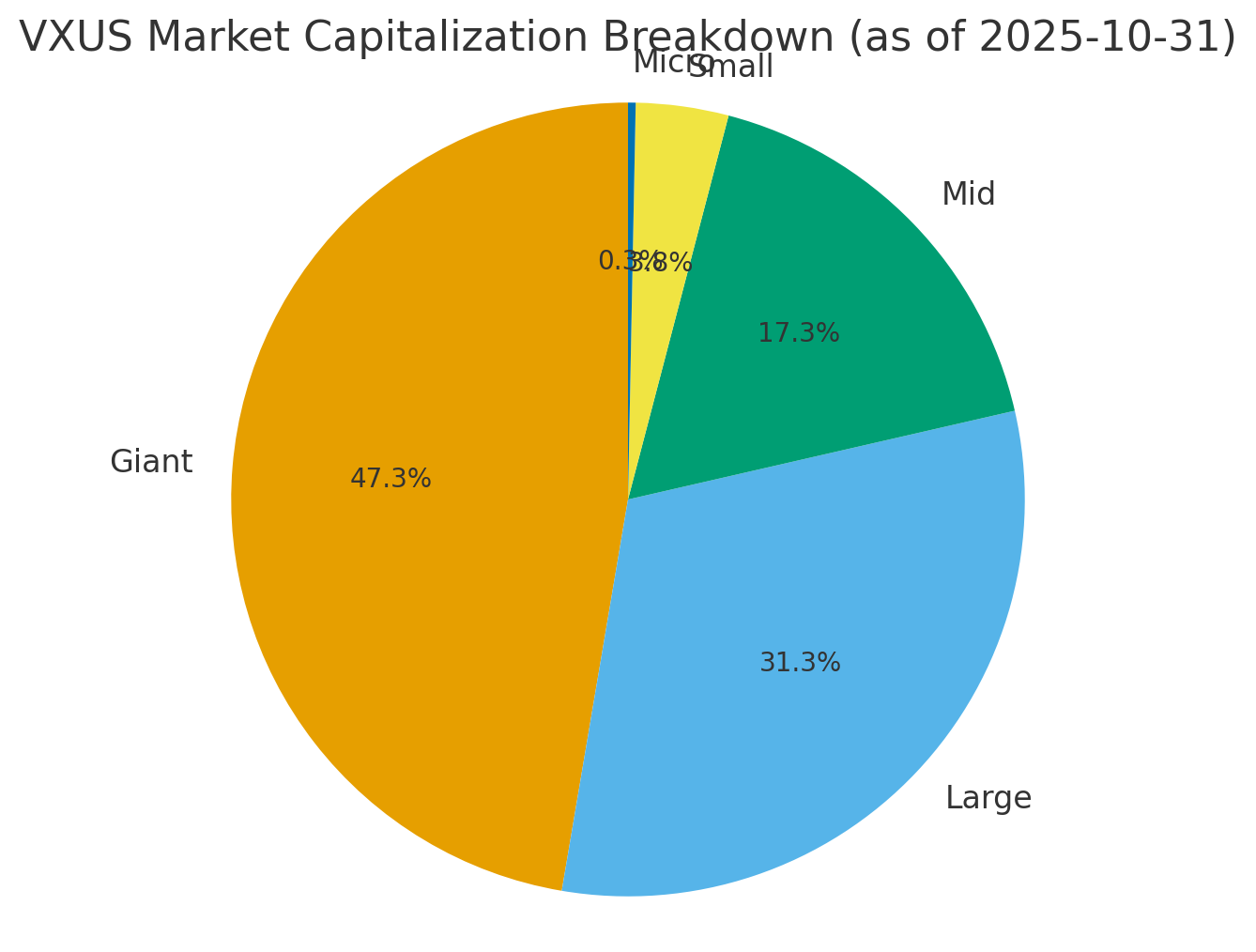

If we take a look at VXUS (Vanguard Total International Market) or another equivalent like Fidelity’s, from a market capitalization standpoint, you can see how it’s broken down in the chart to the right.

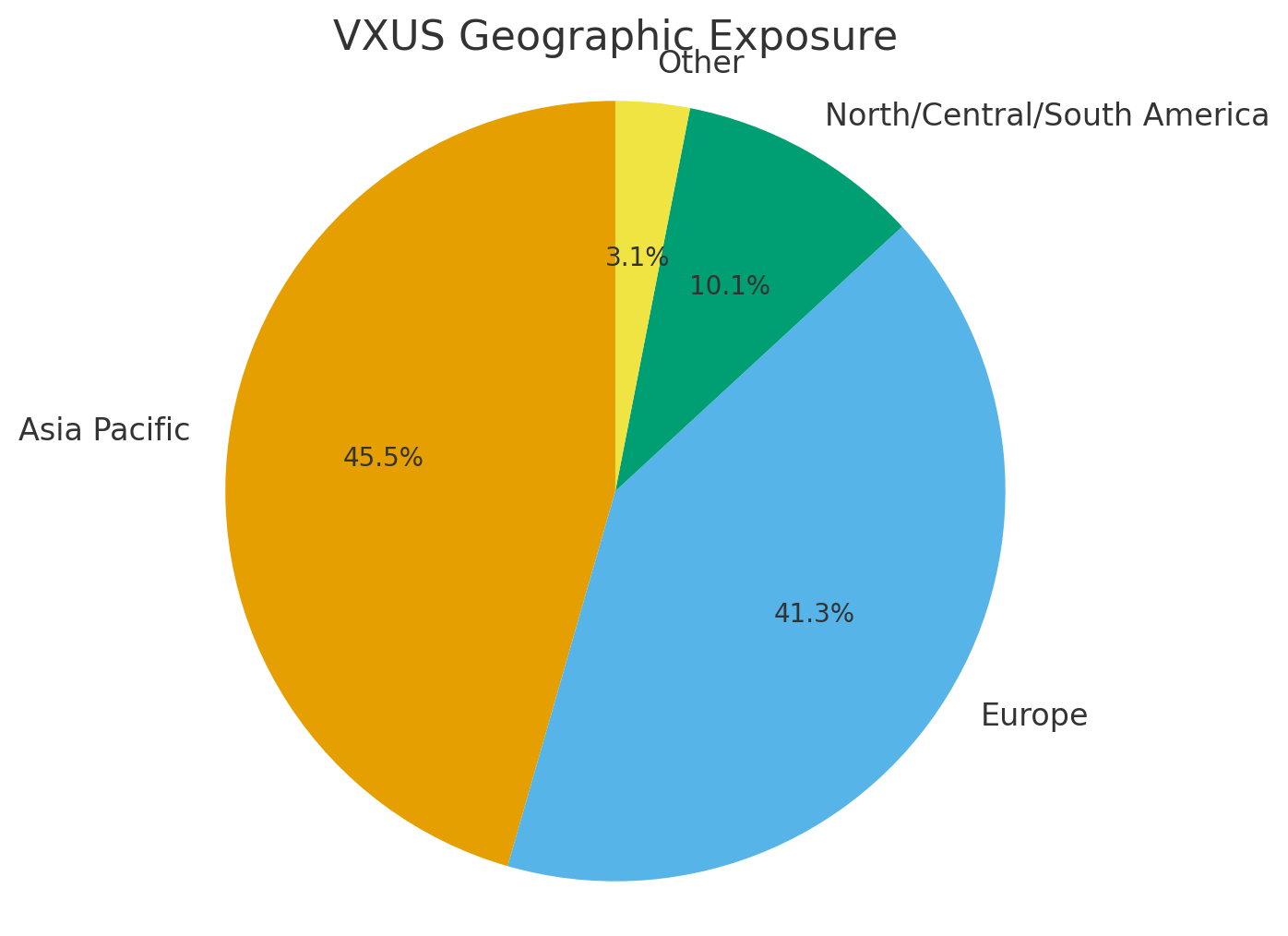

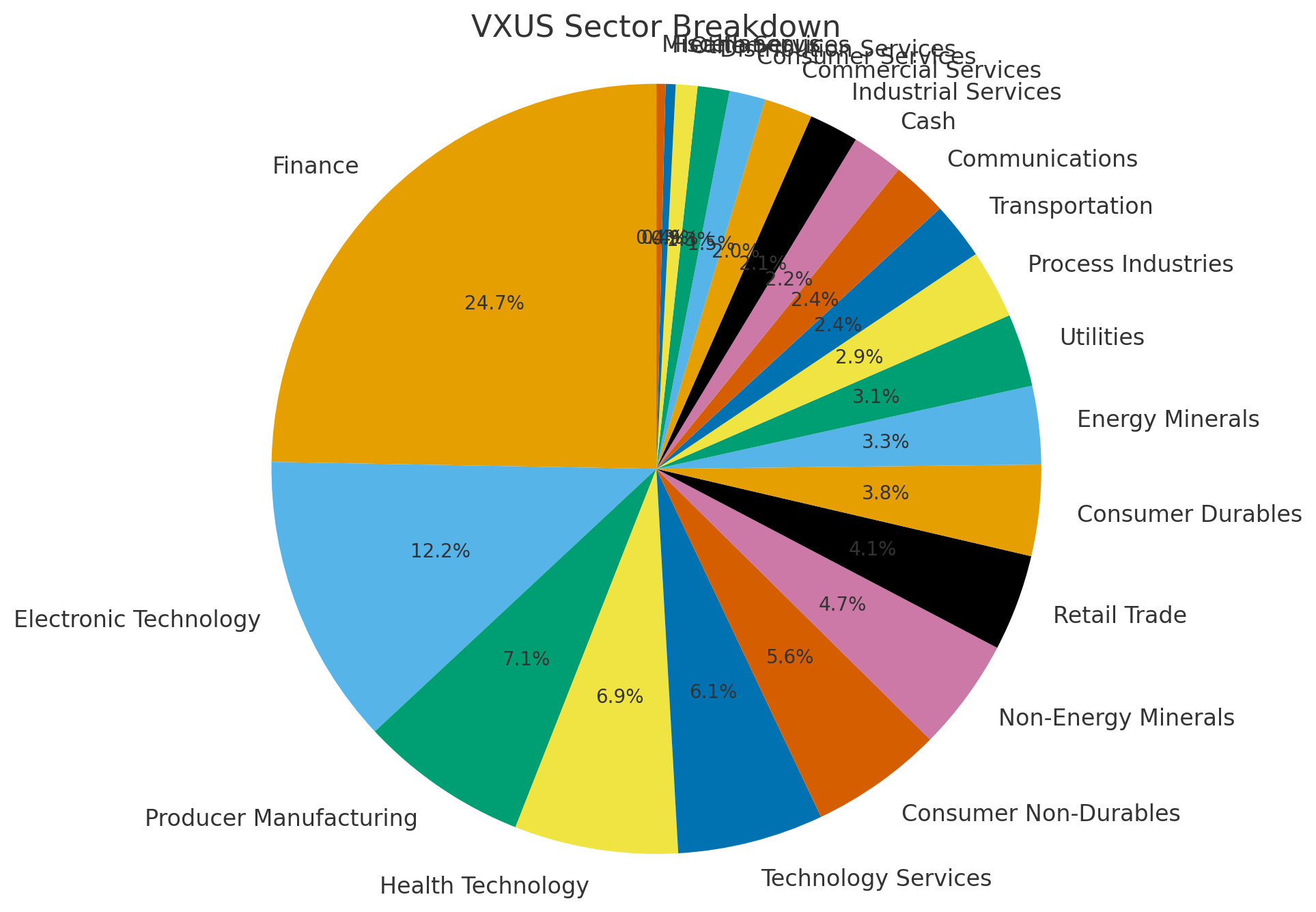

Note: this particular set of pie charts was AI generated, as it is for example purposes only. It should be close to actual numbers, but is suitable for example and explanation purposes.

You can see the breakdown across market cap weighting in action, with a significant chunk of the pie being the biggest companies, followed by one step down, with decreasing percentages across Mid, Small and Micro-cap stocks in the international market.

When we drill in further, we can also see how they are geographically distributed, and even down to their sector coverage, which for a quick comparison, is weighed much higher on finance compared to, for example - the US SP500 Index or other US funds which as of right now tend to heavily lean on Technology in the 35-40% range.

Now, you may have a strong belief, for whatever reason, or none at all, that emerging markets (India, China, South Korea, Thailand, and 10 or so more) are going to be growing significantly over the next 10 years or more. You will get some coverage via VXUS which has approximately 25% coverage in emerging markets, and index funds like VXUS or similar, do rebalance themselves so if/as emerging markets start to grow and outperform their ‘neighbors’ the amount of emerging market exposure will also grow - one of the benefits of market-cap weighted index funds.

But if you had a strong feeling, to the point you wanted to go in a bit heavier on emerging, knowing it along with all of the market, it’s potentially increasing risk, you could do one of two things:

-

Keep overall percentage of ‘Foreign Equities’ the same as your asset allocation but reduce your VXUS holdings by a few percent, or add additional money (or auto-deposit/purchases) towards a higher skewed emerging markets fund such as SCHE or IEMG, or others.

-

Keep your allocations holdings as they are, and use your 1-10% dealers choice to additionally invest in SCHE, IEMG or other.

The first option will result in the same overall exposure to International vs what you had previously, but a larger percentage, or ‘tilt’ in Emerging Markets, while the second will increase International exposure for overall allocation as a result of the addition of more emerging market holdings. This is ok, as we’re generally looking at relatively small percentages, and you can decide if a rebalance is later warranted or not (e.g. US vs International percentages, overall stock holdings, etc.) or if it’s a small enough change to run as is.

Of course this applies to virtually any permutation, e.g. healthcare, real estate, technology, financial tilts, or even specific regions like South Korea.

What you don’t want to do is try to specialize ‘everywhere’ and making a huge mess - after all, your 3 fund index portfolio already has exposure nearly everywhere.

I’ll recommend once again, if you decide to do a ‘tilt,’ keep a majority percentage of your holdings in the 3 fund portfolio funds and limit the tilt to no more than 10% unless you truly know what you’re doing.

One last thing

There’s a lot here. Don’t worry if you feel overwhelmed - start again back at the basics - get your base allocations set up, accounts set up with auto-deposits and auto-purchasing, then come back to this or any other section.

After all, part of the 3 fund philosophy is set and forget, so we can live our lives instead of micro-analyzing every permutation of daily trading ranges or future maybes, while building our future wealth.