Investing Monitoring, Rebalancing and Tax Loss Harvesting

You’ve got your retirement and tax advantaged accounts set up, a brokerage account with auto-deposit and auto-investing and are in the home stretch now (if not, see prior articles in this series!!) and very close to ‘set it and forget it,’ at least as close as self-managed investing comes.

Let’s go through what’s remaining.

Investments need minor tune-ups over time

Just like with your vehicle, investing requires occasional PMS/preventative maintenance and tune-ups. The good news is once you make sure everything is set up properly (refer to prior articles if need be), have auto-deposit and auto-investment enabled, you’re really just ‘checking in’ every 12 months or so. This should include ALL accounts - which you may have consolidated for sanity into for example, a single employer sponsored retirement account, and then perhaps other accounts (IRA, taxable brokerage, 529 College Savings, etc.) at a second institution like Fidelity or Vanguard, and then a single bank account which you may not be using as much any more if you shifted to something like a Fidelity CMA as well. If you have more, it’s OK, but make sure you do check in on all accounts.

There are 3 components to your checks:

-

Monitoring - making sure there are no surprises

-

Re-balancing - adjusting to retain/keep on your core asset allocation ratios/percentages

-

Tax loss harvesting for taxable brokerage accounts - this gives us a way to offset some of the gains that might otherwise increase your taxes

Monitoring

After you have your auto-deposit and auto-invests going and confirmed to be working (please do this at least when setting things up you don’t want to come back a year later to uninvested cash!!!), you still want to do an occasional check-in. This is primarily to check for ‘no surprises’ that things continue to be invested, and to see in general how things are going. I would advise limiting this to no more than quarterly, and to resist the temptations to change things significantly, but as we’ll dig into in the next section, rebalancing, if you decide after a few check-ins that you’re getting out of balance (e.g. your asset allocation ratios are skewing significantly, you can consider making minor adjustments to your auto-investment allocations with new inbound deposits.

Remember the prior comments about the best performing portfolios are often those completely left alone and ‘ignored’ without changes. In addition, if you get tempted to sell assets before holding them for a full year in a taxable account, you’ll be hit with short term gains that get taxes at your normal income rate, versus holding for a year or longer at least puts the gains into a reduced tax rate. For retirement funds and similar tax-advantaged accounts, you can make changes without tax concerns, but again, think long and hard before making significant adjustments.

Rebalancing

Even if you are completely hands off and not even monitoring (once you ensure direct deposits and making it through and auto-investing is working as expected), which isn’t a bad idea (recall that often the most-performant portfolios are simply - hands-off?), you will want to make sure to at least log in to your accounts once a year for checking if a rebalance is needed and for tax loss harvesting.

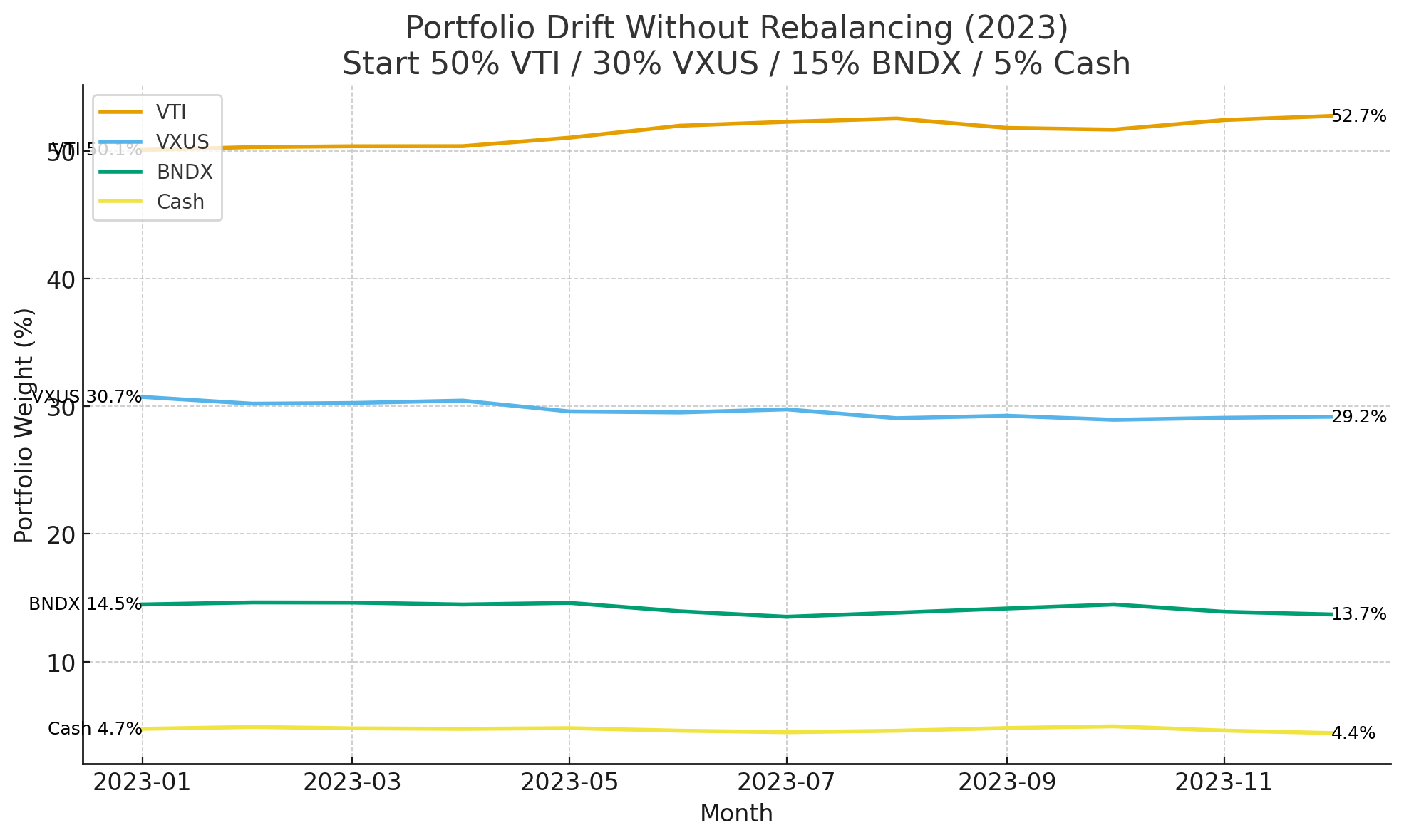

Over time you may find your asset allocation ratio drifting, as one of the 3 or 4 groups (US equity, International Equity, Bonds, Cash/Cash equivalents) may outperform the others. You can see this in the chart below which is using some should-now-be-familiar funds and an aggressive allocation at 50% US Equities (VTI), 30% International(VXUS), 15% Bonds(BNDX) and cash/near-cash holdings.

You can see that over time, you’ll start to drift off of your ratios, which unless you’re in a very different mindset such as ‘100% US SP500 and nothing else), you may want to consider adjusting to get the ratio back on track. In the below chart, you can see real data from 2023 with a ‘should be recognizable’ composition, in this case mostly ETFs (VTI and VXUS) and with a bond mutual fund (this really should be just BND, but the data was a bit annoying to get for the plot so we’ll use BNDX for the example), which starts out at a 50% VTI/US, 30% VXUS/International, 15% Bonds(BNDX) and 5%) cash. The numbers were more or less spot on at the start of the year (the tiny fractional differences are down to buying for example, whole shares, or specific dollar amounts - you shouldn’t be worry on being 100% exact, and +/- .5% is pretty much ‘close enough,’ but you can see the VXUS allocation drifted up by almost 3%, the VXUS/International by almost 1%, and dons by around 1%.

That doesn’t seem like much - should I care?

There are several ways to look at this, ranging from being overly obsessive-compulsive and ‘must hit the right numbers’ down to decimal points, which ironically is going to be counter-productive, at least if you need to sell some assets to adjust the ratio, not to mention likely leading to compulsive monitoring or the portfolio(s), and the temptation to ‘touch’ beyond balancing.

Personally, I don’t worry about a few percentage points of drifts. For one, it’s just too much fiddling on what generally works best mostly being left alone. Second, at least for taxable accounts, we’re going to want to do some tax loss harvesting once a year, so why not combine rebalancing along with tax loss harvesting, using the loss harvesting to adjust what is reasonable, but otherwise only adjusting once it reaches 3-5% of drift in the bigger allocations? (US vs International, and all Stocks vs bonds and cash?

If you are self-managing allocations (for either taxable or tax-advantaged accounts) in different amounts, you can adjust your allocations, or add new money to do the adjustments, or sell US or International Stock to bring up the other one or bonds. You are generally selling off the higher performing assets to buy into the lesser performing ones. However, when you think about it, isn’t this exactly the definition of ‘buy low, sell high?’ The reason for ‘with new money if possible’ is for taxable accounts, so you don’t incur additional taxable gains as a result of the re-balancing. This is somewhat of a balancing act itself, as some may have a chunk of cash or near-cash holdings they can use beyond adjusting auto-investment allocations, and some may need to sell off some assets to re-balance. Do the best you’re able to - at the very least adjust allocation percentages, but you may need to more actively monitor accounts to make sure you don’t over-correct or re-adjust allocations again.

Do be aware that depending on your specific fund selection, there may be some transaction fees - primarily in some of the mutual funds which best belong in tax-advantaged accounts, and usually only when you are buying something like VTSAX from Fidelity or vice versa for Fidelity’s Total Market Index Fund FSKAX if with Vanguard, which if you set up from the prior articles, you didn’t do, and if you had prior holdings, you can always allocate new funds into the equivalent fund without any purchase or sales fees.

Tax Loss Harvesting

This one applies only to taxable accounts, as IRAs, 401ks and tax-advantaged accounts shield you from tax being owed year to year and are only taxed on later withdrawals. If you have a taxable/brokerage account, along with things like a HYSA, banks CDs, and similar, they all may give a net gain via dividends, interest, or short-term or long-term capital gains. Also if you sell assets in a taxable account, that too will incur short term (if held for less than a year) or long-term (held 1 year or longer) capital gains, the former taxed at your normal income rate and the latter being at a lower tax rate, but still net gains that are added to your normal income as taxable adjusted income. Note that some gains may be shown as ‘qualified’ or tax-exempt - don’t worry about these, you’re looking for the short and long term taxable gains.

Your specific brokerage very likely has an option to show ‘gains this year,’ ‘Total Realized Gains YTD’ or similar, which can help out here.

Let’s say that for the year, your brokerage holdings produced $1,000 in long-term gains. You could say, ‘well, that’s not too much, it’s only $150 in taxes’ (actual rate will depend on your tax bracket, but if in the 22% bracket, it’s probably going to be 15% for long term capital gains). You can manually add up your bank dividends if need be, and add that into the total. If you’ve incurred realized losses (which you shouldn’t if we’re holding for a significant saving event or retirement), those will already be deducted in the brokerage’s ‘YTD gains’ calculations.

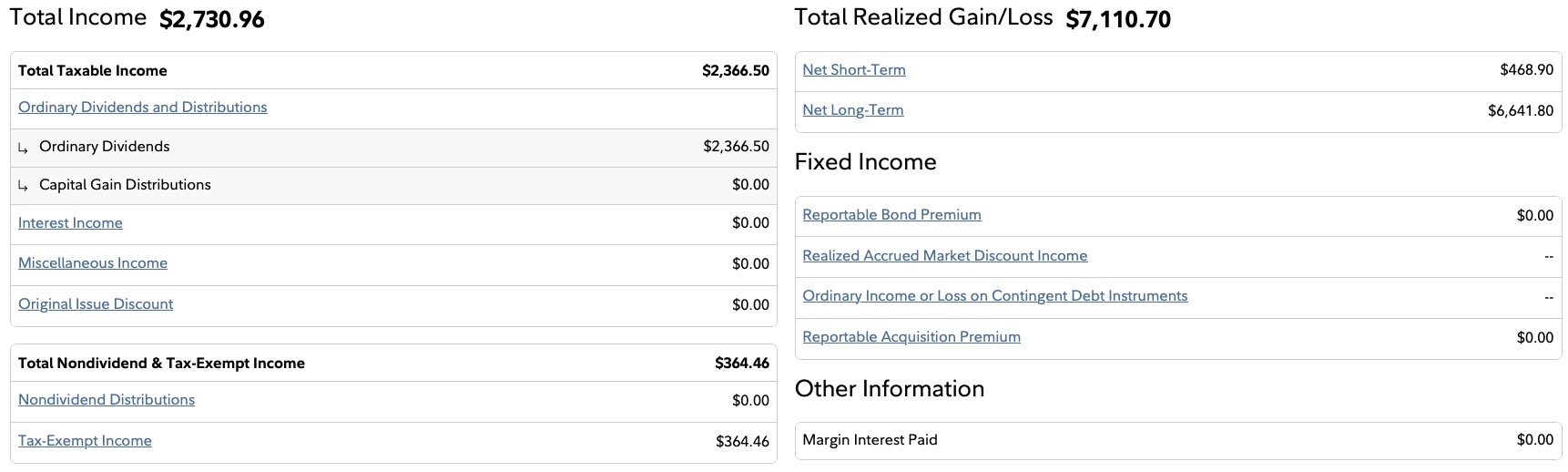

You can see an example below of a YTD statement although not a final year end. You will likely also see similar in your monthly/quarterly and year-end statements.:

You can see the qualified/tax-exempt gains in the lower left, normal dividends in the upper left, then the net short and long-term gains in the account, all totaled up nicely into the total realized gain/loss, in this case a bit over $7000. Left alone that would be added to normal income, but generally without paying into Federal and/or State taxes like your paychecks do. Most of us would prefer not to pay more taxes, and thankfully this is how we reduce it.

The short version here is if we can sell other assets to realize a loss of $7110, it effectively brings your added taxable income to - zero. Short-term losses will first be applied to short-term gains, but then will apply to long-term gain reduction. Likewise, long-term losses will first be applied to long-term gain reduction, but if zeroed, will then be applied to short-term gains.

But wait; there’s more!

Once you effectively zero out any taxable gains, if you have additional realized losses (which usually means a sale of some asset), you can offset up to an additional $3000 from your normal income for that tax year!!

Obviously this depends on your specific portfolio and situation. The reason in this case in prior years I had a large-ish gain in taxable was from inherited a handful of funds, some of which really didn’t belong in a taxable account (mutual funds and dividend focused funds), so I did a one time ‘mostly correct it,’ while I had some other holdings that made little sense, along with some crappy prior company stock, that I knew I’d be able to offset the gains with. So effectively I did a combination rebalance but also a swap for more efficient, cheaper, better performing funds, and kicked out some true long-term losers. Everyone’s situation is different, and if you are doing your rebalancing and harvesting at the same time of year (e.g. December), be aware of the inter-relationships (selling profitable holdings generate a gain), but you can get through both. You may not have enough to offset all gains, but you should try as is possible and reasonable, while also re-balancing if your allocations are drifting too much.

IMPORTANT: When you sell an asset for a loss, you can not buy the same asset or substantially identical one again within 30 days of the sale claiming loss. This is called a ‘wash sale.’ You can still buy it inside of 30 days, but that effectively negates the claim for the loss. This applies across all account holdings, including e.g. if you have multiple brokerage accounts, etc. Short version is if you sell something to claim a loss, buy a near-equivalent if that’s the intent or wait through 30 days before any re-purchase of that specific asset.

Can you make it simpler?

Sure! Once you’re sure your regularly deposited funds are going to the right accounts and being invested as expected, put a day on your calendar for each December to look at any taxable gains incurred and if significant enough, consider offsetting them with losses. If you’re just starting, and can afford the additional tax, stay hands off unless truly dire. If you drift more than 3-5% off your expected allocation ratios, then also re-balance at the same time, just remembering sales with gains in taxable accounts add to your yearly gains, so you may need to additionally offset. Don’t worry about ‘perfect’ on the allocation, especially if also re-balancing, but ‘good enough’ and then go hands off for another 6-12 months and live life.

One last thing

There are a few different ways to look at (for both setting and rebalancing, but they should be done the same way) your overall asset allocation. You don’t necessarilly need to match your allocation ratio in each and every account, meaning - you don’t need to hold your bond allocation in your taxable account, and in most cases, it’s better served in a tax-advantaged one. If you have cash or CDs sitting in a bank account outside of a brokerage account, beyond your savings and normal expenses allotment, that would count towards your cash/short term/bond allocation.

Personally, I’ve got a rolling CD ladder and a second account. I consider the CD ladder to be savings/emergency fund so don’t include it in my investment asset allocations but I do include the other account for overall asset allocation considerations. You may realize you’ve got cash sitting around that could not only be used for the ‘new money’ for rebalancing, or at the very least to make sure you get it into a higher yield option versus sitting in checking. Just be consistent and don’t try to ‘game the system’ as you’re really only gaming yourself.